NR501 Week 2 Reflective Assignment Carper’s Pattern of Knowing Reflective EssayFundamental Nursin

NR501 Week 2 Reflective Assignment Carper’s Pattern of Knowing Reflective Essay

Fundamental Nursing Lessons Learnt from a Difficult Situation in Practice: Carper’s Pattern’s of Knowing in Nursing.

The Practical Situation Experienced

Nursing is about promoting health, preventing illness, and restoring hope. However, there are situations in which a nurse can find themselves almost helpless with regard to all the three above. A case in point is the prospect of having to reassure a patient with terminal illness by giving them hope yet you know very well that they may not have long to live.

Even more daunting is the task requiring you as the nurse to convince the patient and her relatives that they will benefit from hospice care. This is the situation I once found myself in. I was faced with this situation of a 37 year-old who had advanced ovarian cancer with a very poor prognosis. It was obvious that what she needed most in her…

Week 2 Assignment: Reflective Essay

Purpose

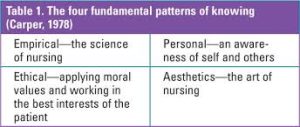

Nursing knowledge is classified in a variety of ways, one of which is Carper’s Patterns of Knowing (Carper, 1978). Carper’s framework offers a lens through which the nurse can reflect upon insights acquired through empirical, ethical, personal, and aesthetic knowledge (Carper, 1978).

Through intentional reflection using Carper’s Patterns of Knowing, nurses can process experiential learning and knowledge acquired through practice. This assignment aims to reflect upon a specific practice situation and better understand the professional knowledge and insights obtained through that experience.

Course Outcomes on NR501 Week 2 Reflective Assignment

Through this assessment, the student will meet the following Course Outcomes:

- Demonstrate logical and creative thinking in analyzing and applying theory to nursing practice. (CO #1)

- Examine broad theoretical concepts as foundational to advanced nursing practice roles. (CO #3)

Requirements

Criteria for Content

- Think of a surprising or challenging practice situation in which you felt underprepared, unprepared, or uncomfortable.

- Select an important nursing issue/topic that was inherent to the identified situation.

- As a method of refection, use Carper’s Patterns of Knowing to analyze the situation. In a two- to three-page paper address the following:

- Briefly explain the situation

- Identify the nursing issue inherent in the identified situation

- What do you think was the underlying reason for the situation? (Esthetics)

- What were your thoughts and feeling in the situation? (Personal)

- What was one personal belief that impacted your actions? (Ethics)

- What evidence in nursing literature supports the nursing importance of the identified issue? (Empirical)

- What new insights did you gain through this reflective practice opportunity?

Preparing the paper

- Application: Use Microsoft Word 2016™ to create the written component of this assessment.

- Length:

- The paper (excluding the title page and reference page) should be at least two but no more than three pages.

- A minimum of two (2) scholarly literature sources must be used.

- Submission: Submit your file to the Canvas course site by the due date/time indicated.

Best Practices in Preparing the Reflective Essay

The following are best practices in preparing this reflective essay.

- Review directions thoroughly.

- Follow assignment requirements.

- Make sure all elements on the grading rubric are included.

- Rules of grammar, spelling, word usage, and punctuation are followed and consistent with formal, scholarly writing.

- Because the paper is a reflective essay, first person is acceptable for this assignment.

- Title page, running head, body of paper, and reference page must follow APA guidelines as found in the 6th edition of the manual. This includes the use of headings for each section of the paper except for the introduction where no heading is used.

- Ideas and information that come from scholarly literature must be cited and referenced correctly.

- A minimum of two (2) scholarly literature sources must be used.

- Abide by CCN academic integrity policy.

Example Reflective Assignment on Aboriginal People

As a nurse, my beliefs and attitudes rely massively on my culture because I often apply various socio-cultural principles when delivering patient care. One of the most profound cultural aspects that shape my profession is religion. As a Christian, I have a different worldview regarding diseases and healing. In this sense, I believe that God created humans in his image to enjoy his companionship and favor.

However, human’s sinful nature destroyed their relationship with God. As a result, God punishes human races through diseases and other calamities because they shifted from mainstream guidelines (Choudry et al., 2018). Consequently, the only way to rekindle the lost love and companionship is through repentance and acknowledging Jesus’s role in restoring humankind.

Alongside Christian narratives of creation, fall, redemption, and restoration, my culture requires people to show impartiality, justice, and love to others. Arguably, these ethical guidelines blend well with the principles of evidence-based nursing practices.

In this sense, the evidence-based practice model (EBP) requires healthcare professionals to encourage justice, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and patient autonomy (Lulé et al., 2019). The ability to incorporate my beliefs and attitudes into the nursing profession is fundamental in enhancing my cultural competence to understand other people’s needs without providing biased care.

Cultural competence is crucial for care providers because it helps them understand and integrate cultural intelligence into healthcare delivery operations. Jongen et al. (2018) argue that healthcare professionals must improve cultural competence to serve the needs of a diverse population. On the other hand, Nair and Adetayo (2019) present cultural competence as “the ability to collaborate effectively with individuals from different cultures, and such competence improves healthcare experiences and outcomes.”

I believe that understanding other people’s cultural values and beliefs is the basic step of incorporating social determinants of health in mainstream care delivery. As a result, it is possible to understand factors that affect the underserved populations facing various healthcare concerns because of socio-economic issues, including low-level education, poverty, low income, and discrimination.

My cultural beliefs and attitudes enhance the desire to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people because I feel that we share core values, including the role of religion in promoting people’s health and wellness. According to Davy et al. (2017), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities share cultural aspects that validate the synergies between culture, land, community, and family in determining people’s well-being.

In this sense, the definition of health for such native communities extends beyond physical and psychological dimensions (Dew et al., 2019). When considering social institutions that promote people’s interpretation of health and well-being among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities, it is valid to argue that any healthcare intervention should focus on capitalizing on unique connections and social institutions.

As a professional nurse determined to work with vulnerable and underserved populations, I believe that process honesty, respect for diversities, effective communication, and awareness are fundamental factors for understanding social determinants for these communities. Fortunately, my cultural beliefs and values encourage commitment, persistence, humility, and honesty when interacting with people from different cultures.

Social Responsibility to Work for Changes in Aboriginal Health

As a nurse, I have a social responsibility to work for changes in Aboriginal health because native communities face various challenges when accessing mainstream healthcare services. According to Davy et al. (2017), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people experience a similar prevalence of chronic diseases to people in developing countries, although Australia is a developed country with a relatively well-funded healthcare system.

In this sense, chronic diseases such as cardiovascular conditions and diabetes are the leading causes of death in these communities. Also, kidney diseases pose higher risks to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people compared to non-Indigenous Australians.

Arguably, many reasons explain health disparities among indigenous Australians, such as Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Wilson et al. (2020) argue that such large gaps in disease and life experiences between indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians rely massively upon poorer determinants of health, discriminatory practices, and the history of marginalization.

Undoubtedly, these factors compromise people’s access to health care and highlight the essential role that healthcare professionals should play in enabling Aboriginal patients to participate in quality healthcare services.

Although the history of marginalization, discriminatory practices, poor social determinants of health, and exclusion affect how native Australians access healthcare services, it is essential to approach such a situation from a positive perspective. In this sense, evaluating community potentials and avenues that determine their well-being is fundamental.

According to Wilson et al. (2017), Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people have a robust and rich history because they are among the oldest cultures in the world. Essentially, their endowed cultural values and beliefs are vital in demonstrating strength, resilience, and tenacity. Also, these communities rely massively upon social systems and cultural institutions such as religion and families as the primary aspects of health and well-being.

Undoubtedly, the presence of firmly held socio-cultural beliefs and practices among indigenous Australians presents various viable opportunities for allied health professionals to create changes. Firstly, I believe that allied health professionals (HPs) and Aboriginal health workers should collaborate in determining the trajectories of healthcare systems.

However, working closely with Aboriginal health workers and community members requires cultural competence because of the potentially varying socio-cultural aspects (Jongen et al., 2019). One of the basic requirements for allied health professionals working with indigenous communities is understanding the implications of colonialism history to health.

Taylor et al. (2020) argue that colonization had a devastating impact on traditional lifestyles because it led to lower education levels, unemployment, shorter life expectancy, and health disparities. As a result, nurses should understand these historical developments to develop informed healthcare frameworks for addressing poorer social determinants of health.

As I endeavor to work with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, I must deconstruct the conflicting opinions that allied health professionals lack culturally appropriate healthcare frameworks to mainstream care services to the underserved population in Australia. For instance, I believe that such a perception persists because of normalizing discriminative healthcare services, where indigenous people receive poor services compared to non-Indigenous Australians.

As a result, effective collaboration between healthcare professionals, high-level cultural competence, and evidence-based practice are crucial approaches to reducing health disparities among native communities (Nash & Arora, 2021). I am confident that I have a social responsibility to act as a change agent in improving the health trajectory of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people by engaging them in nursing research, advocating for their inclusion in mainstream Australian healthcare, and encouraging high-level cultural competence.

NR501 Week 2 Reflective Assignment References

Choudry, M., Latif, A., & Warburton, K. (2018). An overview of the spiritual importance of end-of-life care among the five major faiths of the United Kingdom. Clinical Medicine, 18(1), 23-31. https://doi.org/10.7861/clinmedicine.18-1-23

Davy, C., Kite, E., Sivak, L., Brown, A., Ahmat, T., & Brahim, G. et al. (2017). Towards the development of a wellbeing model for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples living with chronic disease. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2584-6

Dew, A., Barton, R., Gilroy, J., Ryall, L., Lincoln, M., & Jensen, H. et al. (2019). Importance of Land, family, and culture for a good life: Remote Aboriginal people with disability and carers. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 55(4), 418–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.96

Jongen, C., McCalman, J., & Bainbridge, R. (2018). Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5

Jongen, C., McCalman, J., Campbell, S., & Fagan, R. (2019). Working well: strategies to strengthen the workforce of the Indigenous primary healthcare sector. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4750-5

Lulé, D., Kübler, A., & Ludolph, A. (2019). Ethical Principles in patient-centered medical care to support quality of life in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Frontiers In Neurology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00259

Nair, L., & Adetayo, O. (2019). Cultural Competence and Ethnic Diversity in Healthcare. Plastic And Reconstructive Surgery – Global Open, 7(5), e2219. https://doi.org/10.1097/gox.0000000000002219

Nash, S., & Arora, A. (2021). Interventions to improve health literacy among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples: a systematic review. BMC Public Health, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10278-x

Taylor, E., Lyford, M., Parsons, L., Mason, T., Sabesan, S., & Thompson, S. (2020). “We’re very much part of the team here”: A culture of respect for the Indigenous health workforce transforms Indigenous health care. PLOS ONE, 15(9), e0239207. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239207

Wilson, A., Kelly, J., Jones, M., O’Donnell, K., Wilson, S., Tonkin, E., & Magarey, A. (2020). Working together in Aboriginal health: a framework to guide health professional practice. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05462-5

Fundamental Nursing Lessons Learnt from a Difficult Situation in Practice: Carper’s Pattern’s of Knowing in Nursing

The Practical Situation Experienced

Nursing is about promoting health, preventing illness, and restoring hope. However, there are situations in which a nurse can find themselves almost helpless with regard to all the three above. A case in point is the prospect of having to reassure a patient with terminal illness by giving them hope yet you know very well that they may not have long to live.

Even more daunting is the task requiring you as the nurse to convince the patient and her relatives that they will benefit from hospice care. This is the situation I once found myself in. I was faced with this situation of a 37 year-old who had advanced ovarian cancer with a very poor prognosis. It was obvious that what she needed most in her last days would be round-the-clock hospice care for especially pain relief.

The task, therefore, of convincing her together with her relatives to follow this route fell on me. Needless to say, I felt not only unprepared, but also uncomfortable because I knew there was no hope of her surviving for long. Yet I had to give her a reason to look forward to the next day.

The nursing issue inherent in this situation was the need for apt, caring and tactful guidance and counselling as an important role of me as the nurse in this end-of-life situation. I had to not only help the patient and her relatives make the right decision of checking into a hospice, but also give them convincing reasons why they needed to do so. This was not an easy mission to accomplish.

Reflection on the Situation Based on Carper’s Patterns of Knowing

Four facets of nursing knowledge have been identified as empirics or the scientific basis of nursing, esthetics or the consideration of nursing as an art, ethics or the morality in nursing, and the personal knowledge component of nursing (Carper, 1978; Schmidt et al., 2003). On empirics, therefore, I needed to be armed with evidence that hospice care indeed is beneficial for this patient and her family.

This is the evidence that I needed to base my argument on in trying to convince them to accept hospice care. Quaglietti, et al. (2004) have stated that the palliative care offered in the hospice takes care of the patient’s and her family’s expectations in terms of care. They continue that nurse practitioners (NPs) are well placed to meet these expectations.

On esthetics, empathy is the single most important factor in mastering the art of offering nursing care to patients (Carper, 1978). This was the underlying reason for the situation – need for empathy. Experience had taught me that to gain the patient’s trust and confidence; I as the nurse must feel genuine empathy for them. This way they will make less effort to accept any proposal such as going into hospice care.

On personal knowledge, Carper (1978) identifies interpersonal interaction as the barometer with which this knowledge is measured and gained. In this scenario, my personal feeling was that I had to relate with both the patient and her relatives at a personal level by establishing a personal bond with them. In doing this, I had to first know myself and confront my own personal fears and shortcomings.

Last but not least on ethics, I had to be aware that I had a moral obligation to only offer suggestions that would bring the greatest good to the patient and by extension her family (beneficence). Also, whatever suggestion or intervention that I suggested had to be devoid of the possibility of causing harm to the patient (nonmaleficence). But, most importantly, it dawned on me that I had to respect the decision of the patient and her relatives at the end (respect for autonomy) (Haswell, 2019).

Summary

This experience was indeed rich in knowledge for me. I learnt that the four factors of nursing knowledge are present in all practical nursing situations. Thus the double insight I got was the importance of evidence-based practice decisions and the power of empathy. Intentional reflective nursing practice is therefore imperative for improved future care.

References on NR501 Week 2 Reflective Assignment

Carper, B.A. (1978). Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. Retrieved 8 September 2019 from

https://www.google.co.ke/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8871/eb88fb06168bb31e20e9c54e57920e575a47.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwje0JrqscHkAhVClFwKHYXzAgsQFjAQegQICRAB&usg=AOvVaw0CEuuz-eqnIwVMqcmUI55E

Haswell, N. (2019). The four ethical principles and their application in aesthetic practice. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing, 8(4), 177-179. Doi: 10.12968/joan.2019.8.4.177

Schmidt, L.A., Nelson, D. & Godfrey, L. (2003). A clinical ladder program based on Carper’s fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. JONA, 33(3), 146-152. Doi: 10.1097/00005110-200303000-00005

Quaglietti, S., Blum, L. & Ellis, V. (2004). The role of the adult nurse practitioner in palliative care. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 6(4), 209-214. Doi: 10.1097/00129191-200410000-00009

Solution:

It's easy, but reach out anytime if you encounter any difficulties at any point.

WhatsApp boutessays@gmail.com

NEED A UNIQUE PAPER ON THE ABOVE DETAILS?

Order Now

GET HELP INSTANTLY

Place your order to get best research help